Bighorn Sheep Restoration – Get Involved

Ovis canadensis:

Above photo from California Department of Fish & Wildlife utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

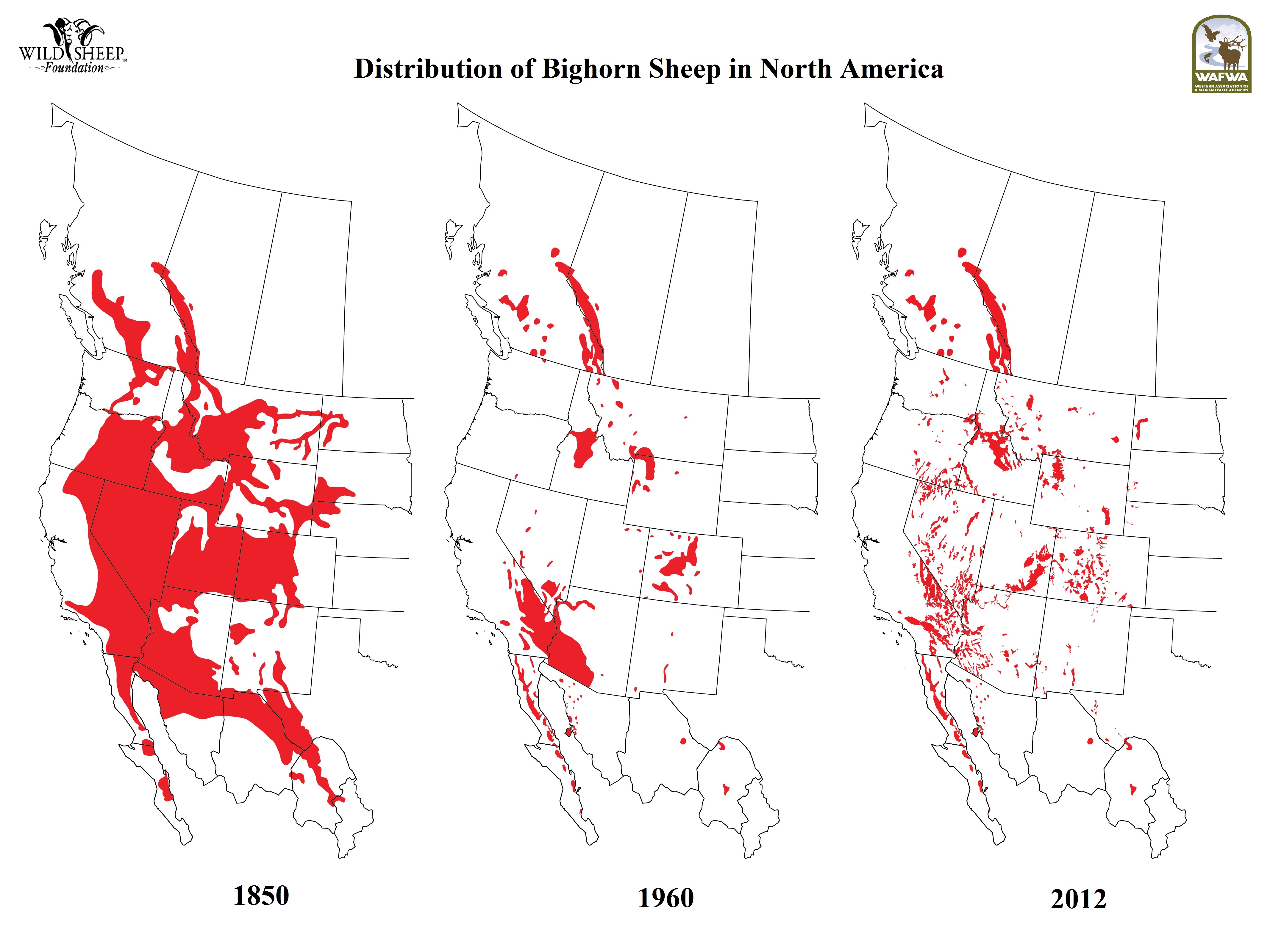

Distribution Map:

Click to Enlarge:

Above map from Western Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies utilized respectfully according to Fair Use.

Population & Recovery Efforts:

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were between 1.5 million to two million bighorn sheep in North America. Today, there are less than 70,000. [1]

Much as the bison did for many native tribes, bighorn sheep were sources of food, clothing, and tools for tribes in the mountainous regions of the west. Petroglyphs featuring bighorns are among the most common images across all western U.S. states.

Above photo from Getty Images utilized respectfully according to Fair Use.

By 1900, encroachment from European settlers diminished the population to several thousand. Bighorn sheep have made a comeback thanks to a conservation movement supported by 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, reintroductions, national parks, and managed hunting. Unfortunately, some subspecies, such as Ovis canadensis auduboni of the Black Hills, were driven into extinction. [2]

Bighorn sheep were once widespread throughout western North America. By the 1920’s, bighorn sheep were eliminated from Washington, Oregon, Texas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and part of Mexico. Today, populations have been re-established through transplanting sheep from healthy populations into vacant places. [1]

Historic 1930s campaigns to save the desert bighorn sheep have resulted in the establishment of two bighorn game ranges in Arizona: Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.

Hunters, not taxes, pay for bighorn sheep conservation and restoration efforts. Funds are derived from the purchase of hunting licenses and tags and indirectly through an excise tax on sporting goods.

Today and in the past, the efforts of conservation groups have also served to increase awareness and “petition” to place certain sub-species like the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep on the Endangered Species List. [2]

The population of peninsular bighorns hit a low of about 280 animals in 1996. Since then, thanks in large part to their inclusion on the federal endangered species list, their numbers have increased to about 600—offering hope that this nimble mountain dweller won’t fall off the precipice. [1]

In Canada, more than 4,500 Rocky Mountain bighorns are fully protected within five National Parks (Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, Waterton, Yoho). An even larger number receive some level of protection in provincial parks and other protected areas in Alberta and British Columbia. Animals in protected areas are often especially vulnerable to poaching because they are habituated to humans and are also readily accessible. Outside national parks, both subspecies of bighorn sheep are covered by provincial or state wildlife acts, and many populations can be hunted under license. Harvesting both adult males and adult females may be permitted in some populations. Hunting quotas are determined each year, and in general regulations are strictly enforced. Management consists of regulating annual harvests, habitat improvement, annual censuses, translocation of animals, and promoting research. Between 200 to 250 male and 150 to 200 female Rocky Mountain bighorns are harvested annually in Alberta. In British Columbia, where only males are hunted: 60 to 65 Rocky Mountain and 40 to 45 California bighorns are shot each year, mainly by resident hunters (Hebert et al., 1985). In much of Canada, male harvest is limited only by the availability of adult males that have reached a minimum curl size, possibly leading to artificial selection against large-horned rams (Coltman et al., 2003).

In the US, Bighorn sheep occur in the following 30 National Parks, Monuments, Recreation Areas and Wildlife Refuges: Arizona: Grand Canyon NP; Cabeza Prieta, Havasu, and Kofa WRs; Glen Canyon, and Lake Mead NRAs; Organ Pipe Cactus NM; California: Sequoia- Kings Canyon NP; Death Valley, and Joshua Tree NMs; Colorado: Mesa Verde, and Rocky Mountain NPs; Colorado, and Dinosaur NMs; Montana: Glacier, and Yellowstone NPs; Bison Range, and C.M. Russell NWRs; Bighorn Canyon NRA; Nevada: Desert NWR; Death Valley NM; Lake Mead NRA; New Mexico: San Andres NWR; North Dakota: T. Roosevelt NP; Oregon: Hart Mountain NWR; South Dakota: Badlands NP; Utah: Arches, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion NPs; Dinosaur NM; Flaming Gorge, and Glen Canyon NRAs; Wyoming: Grand Teton, and Yellowstone NPs; Bighorn Canyon NRA. It also occurs in the large Anza-Borrego State Park (California). Most of these protected areas are in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, and on the Colorado plateau. Numerous other federal lands administered by the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management also contain bighorn. Fourteen state wildlife agencies have transplanted sheep onto more than 200 historic ranges. This has accounted for much of the recovery of bighorn sheep from historic low numbers in the 1960s. However, numerous other transplants have failed (Bailey, 1990), presumably for lack of careful evaluation of habitat conditions at potential transplant sites or because of disease transmitted by livestock. Animals in about half the herds are hunted, and all states with bighorn sheep have at least one hunted population. Usually, only adult males are taken as hunting trophies. The number of sheep permitted to be taken each year is conservative and is regulated by each state. All states require that legally taken trophy heads be marked for permanent identification. This practice allows easy identification of illegally taken animals and thus discourages poaching.

Improvement of habitat for bighorn sheep has been frequent, especially on federal multiple-use lands. Projects have been funded with combinations of federal, state, and private moneys. Natural water sources have been improved and artificial water sources created, especially in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts of the Southwest. Further north, dense forest or shrub vegetation has been cleared, often by controlled burning, to provide open areas with forage for bighorn sheep. Some populations of bighorn are routinely baited and treated with drugs to control parasites including lungworm (Protostrongylus sp.). Such treatments concentrate sheep and may jeopardize wildness. Management and research biologists exchange information on bighorn sheep in annual meetings of the Desert Bighorn Council and biennial meetings of the Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council. Proceedings of these meetings are published. Three private organizations, the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Society and the Society for the Conservation of Bighorn Sheep, raise funds for research and management. At least 10 states auction and/or raffle one or two special bighorn hunting licenses to raise funds for these purposes. Its status within the United States is Not Threatened (but see below).

The status of most traditional subspecies and major ecotypes of bighorn sheep is satisfactory because they exist on 30 biological reserves and on many other protected areas. However, their status is not fully secure because at least 64% of the herds contain about 100 animals. Berger (1990) reviewed the history of some small bighorn populations and concluded that those numbering less than 50 animals usually became extirpated, but Wehausen (1999) provides an alternative interpretation and viewpoint. Further, the ecotypes of bighorn in the Chihuahuan desert and in shortgrass-badlands and riverbreak environments are not secure because there are few reserves or other protected lands within these two regions, and very few of these lands contain wild sheep.

Conservation measures proposed for the United States: 1) Additional research on bighorn diseases, particularly in relation to domestic livestock, and on developing efficient methods for habitat management is desirable. 2) State and federal agencies should develop coordinated plans to enhance the long-term security of the numerous bighorn herds with less than 100 sheep. Strategies should include increasing herd size, expanding habitat and increasing herd mobility, and enhancing habitat quality and habitat protection in corridors between small herds (Bailey 1992). 3) Land management agencies, especially the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, should formally recognize bighorn ranges in their management plans, including corridors for movement within and between herds. 4) Until disease relations are clearer, bighorn should be protected from contact with domestic sheep and domestic goatswhenever possible. 5) Greater recognition of the values and importance of ecotypic variation in bighorn sheep is needed. Federal agencies and state wildlife departments should seek a consensus on classifying the major ecotypes. Each state should furthermore classify its bighorn according to state ecotypes. Conservation of major ecotypes should proceed under the federal Endangered Species Act. Each state should be responsible for conserving another level of ecotypic diversity of bighorn sheep within its boundaries. 6) Increase the number of bighorn sheep in federally protected habitats in the Chihuahuan Desert and in the shortgrass-badlands and river breaks ecosystems. In the Chihuahuan Desert, options include: a) expanding protection of habitat and sheep from the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge to a greater portion of the White Sands Missile Range; b) formally recognizing and enhancing protection of the Big Hatchet Game Range, now on Bureau of Land Management land; c) establishing viable bighorn populations in Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend National Parks; and d) establishing bighorn in a new biological reserve, probably in west Texas. 7) In the shortgrass-badlands and river breaks ecosystems, management options include: a) expanding bighorn populations and distributions in the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, the Bighorn National Recreation Area, and in Theodore Roosevelt and Badlands National Parks; and b) establishing bighorn populations in new biological reserves in eastern Wyoming or western Nebraska. [3]

3 Surviving Subspecies:

-

Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis)

-

Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae), formerly California Bighorn Sheep

-

Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni)

Threats:

- Predators: Mountain lions, coyotes, wolves and bears will all kill mountain sheep if given the opportunity, but chasing the sheep in the cliffs is rarely successful.

- Disease: Disease usually takes a far higher toll among bighorns than predators. [2] Conservationists are struggling to protect bighorn sheep on public lands from disease-carrying livestock (including domestic sheep). [4]

- Accidents: As sure-footed as they are, bighorn sheep sometimes slip and fall from the cliffs or are struck by falling rocks.

- Poaching of large, trophy males. [2]

Hunting, loss of food from livestock grazing and disease from domestic livestock have devastated bighorn sheep populations. While livestock is not as much of a threat as in the past, loss of habitat from development is an increasing threat. Normally, predators like mountain lions, wolves, bobcats, coyotes and golden eagles do not pose a threat to bighorn sheep. However, in areas where sheep populations are low, the death of a sheep from a natural predator can be a risk to the larger population.

Nearly one-third of California’s populations of desert bighorn sheep have died out in the past century. These losses have occurred primarily at lower elevations, where increases in temperature and decreases in precipitation have reduced the amount of vegetation available for foraging and the freshwater springs they depend on for water. More populations of desert bighorn sheep may be at risk as the southwestern climate continues to become hotter and dryer. [1]

Description:

Large, curved horns, borne by the males, or rams, can weigh up to 30 lb (14 kg) – as much as the rest of the bones in the male’s body. Older rams have massive horns that can grow over 3 feet long with more than one foot in circumference at the base!

Above photo from Bing utilized according to Fair Use.

Females, or ewes, also have horns, but they are short with only a slight curvature. Both rams and ewes use their horns as tools for eating and fighting.

Although not as agile as mountain goats, bighorn sheep are well-equipped for climbing the steep terrain that keeps their predators at bay. The outer hooves are modified toenails shaped to snag any slight protrusion, while a soft inner pad provides a grip that conforms to each variable surface.

Behavior:

Mature males spend most of their year in bachelor flocks apart from groups of females and young sheep. Young females generally remain in their mother’s group (led by an older ewe) for life. All ewes are subordinate to even young rams with bigger horns.

Males depart their mother’s group around 2 to 4 years of age and join a group of rams. This is sometimes a tough time of wandering until the young rams find a male group and they will sometimes take up with other species out of loneliness.

Bighorn sheep groups protect themselves from predators by facing different directions, allowing them to keep watch on their surroundings.

Diet:

As ruminants, grass-eating bighorn sheep have a complex four-part stomach that enables them to eat large portions rapidly before retreating to cliffs or ledges where they can thoroughly re-chew and digest their food, safe from predators. Then bacteria takes over, breaking down plant fibers for digestion. The sheep also absorb moisture during this digestive process, enabling them to go for long periods without water.

Lifespan:

Longevity depends on population status. In declining or stable populations, most sheep live over 10 years. Even in areas where no hunting occurs, females rarely make it past 15 and males rarely live beyond 12. Juvenile mortality is variable and can be quite high, ranging from 5 to 30%. Sheep between 2 and 6 years old have low mortality.

Reproduction:

It is during the mating season or “rut” that the rams join the female groups and engage in fierce competition to establish access rights to ewes. Their dominance hierarchy is based on age and size (including horn size), which usually prevents rams younger than seven years old from mating. Younger males will mate sooner if dominant rams in their group are killed.

Mating competition involves two rams running toward one another, at speeds around 40 mph, and clashing their curled horns, which produces a sound that can be heard a mile away. Most of the characteristic horn clashing between rams occurs during the pre-rut period, although this behavior may occur to a limited extent throughout the year.

Most populations undergo seasonal movements, generally using larger upland areas in the summer and concentrating in sheltered valleys during the winter. [2]

References:

[1]: Defenders of Wildlife, “Bighorn Sheep”: www.defenders.org/bighorn-sheep/basic-facts

[2]: National Wildlife Federation, “Bighorn Sheep”: www.nwf.org/Wildlife/Wildlife-Library/Mammals/Bighorn-Sheep.aspx

[3]: Festa-Bianchet, M. 2008. Ovis canadensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15735A5075259. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15735A5075259.en. Downloaded on 29 September 2017: www.iucnredlist.org/details/15735/0

[4]: National Wildlife Federation, “Battle for Bighorn”: www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/National-Wildlife/Animals/Archives/2011/Battle-for-Bighorns.aspx