This page is continued from Wild Willpower’s National Plan >>>> Civilian Restoration Corps >>>> Native Animal & Habitat Restoration (& Wildfire Prevention!) Projects >>>> Paid for via Gradually Transferring the $30 billion per year in Livestock Subsidies:

****************************

i. Factory Farm “Hog Lagoons”

are Poisoning America’s Waterways:

Smithfield Foods, the largest and most profitable pork processor in the world, killed 27 million hogs in 2005. The logistical challenge of processing that many pigs each year is roughly equivalent to butchering and boxing the entire human populations of New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Antonio, San Diego, Dallas, San Jose, Detroit, Indianapolis, Jacksonville, San Francisco, Columbus, Austin, Memphis, Baltimore, Fort Worth, Charlotte, El Paso, Milwaukee, Seattle, Boston, Denver, Louisville, Washington, D.C., Nashville, Las Vegas, Portland, Oklahoma City and Tucson.

Click any photo on this page to enlarge:

Above photo from Getty Images used in accordance with Fair Use.

A slaughter-weight hog is fifty percent heavier than a person, & hogs produce three times more excrement than human beings do. The 500,000 pigs at a single Smithfield subsidiary in Utah generate more fecal matter each year than the 1.5 million inhabitants of Manhattan. Smithfield’s total waste discharges approximately 26 million tons per year. [1] Producing evidence of this, however, has become increasingly difficult in certain states due to the passing of so-called “Ag-Gag Laws” which serve to scare Citizens away from exerting their right to film agro-industrial operations. [2] For example,

Amy Meyer was arrested in 2013

for Photographing the Exterior of a Cattle Feedlot:

Smithfield’s sales estimated $11.4 billion in 2006. So prodigious is its fecal waste, however, that if the company treated its effluvia marginally close to the standard big-city governments do, it would lose money. So, many of its contractors allow great volumes of waste to run out of their slope-floored barns and sit in pools called “lagoons”, where the waste gathers, untreated, & the elements break it down while gravity pulls it into the groundwater and river systems.

Spy Drone Footage of Hog Manure Lagoons from Smithfield Foods:

Footage from SpeciesismTheMovie:

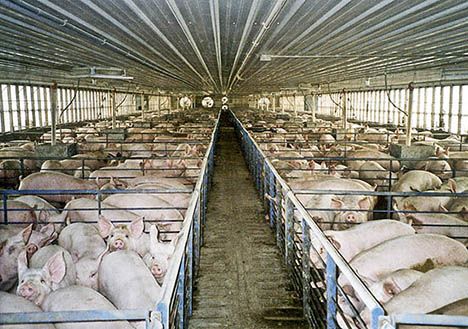

Smithfield’s pigs live by the hundreds or thousands in warehouse-like barns, in rows of wall-to-wall pens, as shown:

Above photo from Farm Sanctuary utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Sows are artificially inseminated, fed and delivered of their piglets in cages so small they cannot turn around:

Above photo from National Geographic utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Forty fully grown 250-pound male hogs often occupy a pen the size of a tiny apartment, often trampling each other to death:

Above photo from One Green Planet utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

There is no sunlight, straw, fresh air, or earth. The floors are slatted to allow excrement to fall into a catchment pit under the pens, but many things besides excrement can wind up in the pits: afterbirths, piglets accidentally crushed by their mothers, broken bottles of insecticide, antibiotic syringes, stillborn pigs – anything small enough to fit through the foot-wide pipes that drain the pits. The pipes remain closed until enough sewage accumulates in the pits to create good expulsion pressure; then the pipes are opened and everything bursts out into a large holding ponds.

Above photo from MFAblog.org utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

The temperature inside hog houses is often hotter than ninety degrees. The air is saturated with gases from manure and chemicals, which becomes lethal to the pigs at times when the enormous exhaust fans, which run twenty-four hours a day, malfunction & cease to operate:

Above photo of factory farm exhaust fans from AgriNews.com utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

The immobility, poisonous air, and stressful conditions compromise the pigs’ immune systems. They become susceptible to infection, and in such dense quarters microbe, parasites or fungi, once established in one pig, can quickly contaminate the whole population. Accordingly, factory pigs are infused with a huge range of antibiotics and vaccines, and are doused with insecticides. Without these compounds – oxytetracycline, draxxin, ceftiofur, tiamulin – diseases would likely kill them. The drugs Smithfield administers to its pigs are present in their manure, and exit the hog barns into the lagoons. Industrial pig waste also contain ammonia, methane, hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide, cyanide, phosphorous, nitrates and heavy metals. In addition, the waste hosts more than 100 microbial pathogens that can cause illness in humans, including salmonella, cryptosporidium, streptocolli and giardia. Each gram of hog manure can contain as much as 100 million fecal coliform bacteria.

Closeup of giardia pathogen:

Above photo from the Center of Disease Control and Prevention used in accordance with Fair Use.

Smithfield’s “lagoons” cover as much as 120,000 square feet. The area around a single slaughterhouse can contain hundreds of lagoons, some of which run thirty feet deep. The liquid in them is not brown, however, as interactions between the bacteria, blood, afterbirths, stillborn piglets, urine, excrement, chemicals, and drugs turn the lagoons pink:

Above photo by Travis Drove of Bloomberg utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Even light rains can cause lagoons to overflow; major floods, on several occasions, have covered counties, contaminating waterways with built up matter which then overflows from the lagoons:

Above photo from Union of Concerned Scientists utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Some hog farm lagoons have polyethylene liners, which can be punctured by rocks in the ground, allowing shit to seep beneath the liners and spread and ferment. Gases from the fermentation can inflate the liner like a hot-air balloon and rise in an expanding, accelerating bubble, forcing thousands of tons of feces out of the lagoon in all directions.

The lagoons are so viscous and venomous, if a person falls in, it is almost certainly lethal. In 1992, when a worker making repairs to a lagoon in Minnesota began to choke to death on the fumes, another worker dived in after him, and they died the same death. In another instance, a worker who was repairing a lagoon in Michigan was overcome by the fumes and fell in. His fifteen-year-old nephew dived in to save him but was overcome, the worker’s cousin went in to save the teenager but was overcome, the worker’s older brother dived in to save them but was overcome, and then the worker’s father dived in. They all died inside the lagoon.

Studies have shown that lagoons emit hundreds of different volatile gases into the atmosphere, including ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide. A single lagoon releases many millions of bacteria into the air per day, some resistant to human antibiotics. Hog farms in North Carolina also emit some 300 tons of nitrogen into the air every day as ammonia gas, much of which falls back to earth and deprives lakes and streams of oxygen, stimulating algal blooms and killing fish:

Above photo from InIndianaWater.org utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

To alleviate swelling lagoons, the viscous liquid content is at times pumped out and sprayed onto surrounding fields, as shown in this photo from a Wisconsin farm:

Above photo from USGS.gov utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

The idea of fertilizing fields with hog manure is borrowed from the past: the small hog farmers that Smithfield drove out of business used animal waste to fertilize their crops, which they then fed to the pigs. Smithfield says that this, in essence, is the same thing tje company does. “If you manage your fields correctly, there should be no runoff, no pollution,” says Dennis Treacy. Smithfield’s vice president of environmental affairs. “If you’re getting runoff, you’re doing something wrong.” At some Smithfield farm, manure can be seen spraying the lagoon’s contents into the air as a fine mist:

Above photo from All-Creatures.org utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

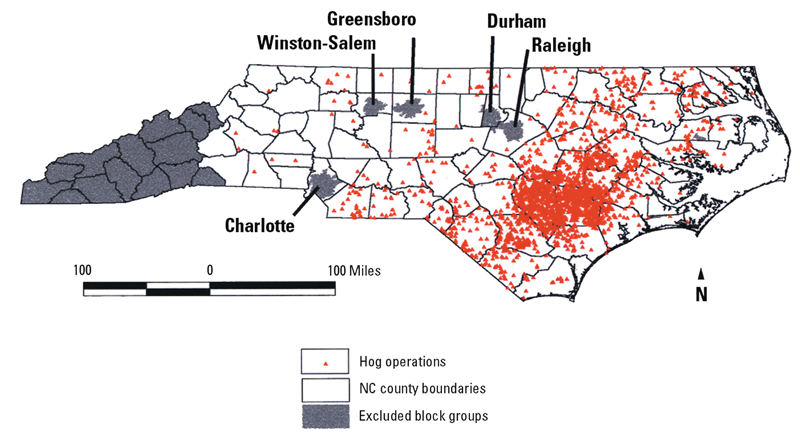

Smithfield doesn’t grow nearly enough crops to absorb all of its hog waste. The company raises so many pigs in so little space that it has to import the majority of their food, which contains large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus. Those chemicals, when sprayed onto fields, run off into the surrounding ecosystem, causing what Dan Whittle, a former senior policy associate with the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, calls a “mass imbalance.” At one point, three hog-raising counties in North Carolina were producing more nitrogen, and eighteen were producing more phosphorus, than all the crops in the state could absorb.

Many people who live near hog farms suffer from bronchitis, asthma, heart palpitations, headaches, diarrhea, nosebleeds and brain damage. In 1995, a woman downwind from a corporate hog farm in Olivia, Minnesota, called a poison-control center and described her symptoms. “Ma’am,” the poison-control officer told her, “the only symptoms of hydrogensulfide poisoning you’re not experiencing are seizures, convulsions and death. Leave the area immediately.” When flying over eastern North Carolina, one will see that virtually everyone in this part of the state lives close to a lagoon:

Above map from North Carolina Health News utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Springs, streams, swamplands and lakes are numerous throughout eastern North Carolina, a coastal plain that is grooved and tilted toward the sea. Smithfield’s fields almost always incline toward creeks or creek-fed swamps. Half-perforated pipes called irrigation tiles, commonly used in modern farming, run beneath many of the fields: when they become unplugged, the tiles effectively operate as drainpipes, dumping pig waste into surrounding tributaries.

A Drain Tile Being Installed:

Above photo by the Peru Gazette utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Many studies have documented the harm caused by hog-waste runoff; one showed the the waste as the primary catalyst for raising the levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in a receiving river as much as sixfold. In eastern North Carolina, nine rivers and creeks in the Cape Fear and Neuse River basins have been classified by the state as either “negatively impacted” or environmentally “impaired.”

Smithfield’s lagoons are historically prone to failure. In North Carolina alone they have spilled, in a span of four years, 2 million gallons of waste into the Cape Fear River, 1.5 million gallons into its Persimmon Branch, one million gallons into the Trent River, 200,000 gallons into Turkey Creek. In Virginia, Smithfield was fined $12.6 million in 1997 for 6,900 violations of the Clean Water Act – the third-largest civil penalty ever levied under the act by the EPA. The fine amounted to .035 percent of Smithfield’s annual sales.

A river that receives a lot of waste from an industrial hog farm begins to die quickly. Toxins and microbes can kill plants and animals outright: the waste consumes available oxygen, suffocating aquatic animals. Later, algal blooms will continue to deoxygenate the water.

Much of Smithfield’s hog waste makes its way into the Neuse River; in a five-day span in 2003 alone, more than 4 million fish died. Hog waste runoff has damaged the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound, which is almost as big as the Chesapeake Bay and which provides half the nursery grounds used by fish in the eastern Atlantic.

In 1995, the dike of a 120,000-square-foot lagoon owned by a Smithfield competitor ruptured, releasing 25.8 million gallons of effluvium into the headwaters of the New River in North Carolina. It was the biggest environmental spill in U.S. history, more than twice as big as the Exxon Valdez oil spill six years earlier. The sludge was so toxic it burned flesh upon contact, and so dense it took almost two months to make its way sixteen miles downstream to the ocean. From the headwaters to the sea, every creature living in the river was killed. Fish died by the millions.

In 1999. Hurricane Floyd washed 120,000.000 gallons of hog waste into the Tar, Neuse, Roanoke, Pamlico, New, and Cape Fear rivers. Satellite photographs show a dark brown tide closing over the region’s waterways, converging on the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound and feeding itself out to sea in a long, well-defined channel. Very little freshwater marine life remained behind. Tens of thousands of drowned pigs were strewn across the land. Beaches located miles from Smithfield lagoons were slathered in feces.

Large industrial hog farming contributes to another form of environmental havoc: Pfiesteria piscicida, a microbe that, in its toxic form, has killed a billion fish and injured dozens of people. Nutrient-rich waste such as hog manure creates the ideal environment for Pfiesteria to bloom: the microbe eats fish that are attracted to the algae that is nourished by the waste. The microbe degrades a fish’s skin, laying bare tissue and blood cells; it then eats its way into the fish’s body. The following excerpt on Pfiesteria is from the documentary Earthlings:

After the 1995 spill, millions of fish developed large bleeding sores on their sides and quickly died. Fishermen found that at least one of Pfiesteria’s toxins could take flight: breathing the air above the bloom caused severe respiratory difficulty, headaches, blurry vision and logical impairment. Some fishermen forgot how to get home; laboratory workers exposed to Pfiesteria lost the ability to solve simple math problems and dial phones: they forgot their own names. It could take weeks or months for the brain and lungs to recover.

Several state legislatures have now passed laws prohibiting or limiting the ownership of small farms by pork processors. In some places, new slaughterhouses are required to meet expensive waste-disposal requirements: many are now forbidden from using the waste-lagoon system. North Carolina, where pigs now outnumber people, has passed a moratorium on new hog operations and ordered Smithfield to fund research into alternative waste-disposal technologies. South Carolina, having taken a good look at its neighbor’s coastal plain, has pronounced the company unwelcome in the state.

These initiatives, however, have come late. Industrial hog operations control at least seventy-five percent of the market. Twenty-six percent of the pork processed in this country is Smithfield pork. [1]

Hog confinements across Illinois also produce massive amounts of manure, with frequent spills blackening creeks, destroying fish, & damaging the quality of life for people in rural communities.

Lagoons sometimes crumble or overflow, causing waste to gush from the hoses and pipes that carry waste to the fields. In some instances, state investigators found polluting was simply “willful”: confinement operators simply dumped thousands of gallons of manure they couldn’t use or sell as fertilizer.

Between 2005 and 2014, pollution incidents from hog confinements killed at least 492,000 fish — nearly half of the 1 million fish killed in water pollution incidents statewide during that period. Pig waste impaired 67 miles of the state’s rivers, creeks and waterways over that time. Hopkins Ridge Farms are among Illinois’ alleged lead polluters according to state officials. [3]

The Mississippi Dead Zone is Fed by Pollution & Fertilizer Runoff:

The Mississippi River Basin collects roughly ten thousand pounds of fertilizer and raw sewage pollution annually from 31 states & some of Canada. Spring & summer rains wash the excessive nutrients in fertilizers & sewage downstream, into the Gulf of Mexico. For a few months every year, the nitrogen- and phosphorus-loaded water feeds massive algal blooms that consume the oxygen available in the water. The oxygen-depleted waters force fish and wildlife to leave, while bottom–dwellers like Gulf shrimp often cannot escape & thus die. Scientists call this oxygen-depleted condition hypoxia, & it is getting worse. [4]

The Dead Zone: a story of seasonal hypoxia near the outflows of the Mississippi River

Video uploaded by Anthony Reisinger:

Researchers from Louisiana State University (LSU) and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) announced that the 8,776 square mile (New Jersey-sized) Dead Zone is the largest Dead Zone on record. The Dead Zone is fueled by fertilizer pollution flowing down the Mississippi River from the American heartland, which cause massive algae blooms. [5]

Map of Dead Zone:

Click to Enlarge:

Above image from SailorsForTheSea used in accordance with Fair Use.

A report by Mighty Earth identifies companies responsible for much of the animal waste & fertilizer pollution that contribute to the Dead Zone, showing that most of it is caused by the vast quantities of corn & soy used to feed cattle, hogs, & poultry. According to the study, America’s largest meat company, Tyson Foods, has the largest footprint. Tyson produces one out of every five pounds of meat produced in the United States. The report found:

- Tyson is the only meat company with major processing facilities in each of the states listed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as contributing the highest levels of pollution to the Gulf;

- Tyson and Smithfield have the heaviest concentration of meat facilities in those regions of the country with the highest levels of nitrate contamination;

- Tyson’s top feed suppliers are behind the bulk of grassland prairie clearance, which dramatically magnifies the impacts of fertilizer pollution, with Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) clearly dominating the market for corn and soy with their network of grain elevators & feed silos in all the states with the highest losses. [6]

ii. Habitat Loss:

Researchers from Stanford University, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and other organizations, representing five countries, presented their findings on Feb. 19, 2017 at the annual meeting of the American Association of the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in San Francisco during a symposium entitled, “Livestock in a Changing Landscape: Drivers, Consequences and Responses”:

Large-scale livestock operations provide most of the meat & meat products consumed around the world-consumption that is growing at a record pace & is projected to double by 2050, said symposium organizer Harold A. Mooney, professor of biological sciences at Stanford.

Grazing occupies 26 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, & feed-crop production requires about a third of all arable land. Expansion of livestock grazing land is also a leading cause of deforestation, especially in Latin America. In the Amazon basin, about 70 percent of previously forested land is used as pasture, while feed crops cover a large part of the remainder. Land once farmed locally is being transformed to cropland for industrialized feed production, with grasslands & tropical forests being destroyed in these land use changes. [7]

References:

[1]: Rolling Stone, “Boss Hog: The Dark Side of America’s Top Pork Producer” by y Jeff Tietz (12-14-2006): www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/boss-hog-the-dark-side-of-americas-top-pork-producer-20061214

[2]: American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (“ASPCA”), “Ag-Gag Legislation by State”: www.aspca.org/animal-protection/public-policy/ag-gag-legislation-state

[3]: Chicago Tribune, “Spills of pig waste kill hundreds of thousands of fish in Illinois” by David Jackson and Gary Marx (9-22-2017): www.chicagotribune.com/news/watchdog/pork/ct-pig-farms-pollution-met-20160802-story.html

[4]: 1mississippi.org, “Dead Zone”: http://1mississippi.org/dead-zone/

Map of Dead Zone & Mississippi River Basin: https://www.sailorsforthesea.org/programs/ocean-watch/ocean-dead-zones

Video: Anthony Reisinger, “The Dead Zone: a story of seasonal hypoxia near the outflows of the Mississippi River”: www.youtube.com/watch?v=TPip2u7byvY

[5]: Gulf Restoration Network, “Dead Zone Bigger than Ever – Report Reveals America’s Largest Meat Companies’ Role in Polluting Gulf of Mexico”: https://healthygulf.org/media/press-releases/2017-08-02-000000/dead-zone-bigger-ever-report-reveals-americas-largest-meat

[6]:1mississippi.org, “Dead Zone Bigger than Ever – Report Reveals America’s Largest Meat Companies’ Role in Polluting Gulf of Mexico”: http://1mississippi.org/dead-zone-bigger-than-ever-report-reveals-americas-largest-meat-companies-role-in-polluting-gulf-of-mexico/

[7]: Stanford University. “Harmful Environmental Effects Of Livestock Production On The Planet ‘Increasingly Serious,’ Says Panel.” ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/02/070220145244.htm (accessed September 1, 2017)

*************************************

Back to The Platform:

Petition – Transfer Livestock Subsidies to Native Animal & Habitat Restoration Projects – Bison, Elk, Antelope, etc.

Related Topics:

- Current Livestock & Feed Crop Subsidies – per year

- Animal Abuse & Subjugation in the Current U.S. Economy

- Habitat Restoration Processes & Organizations Involved

*************************************