Written May 14, 2025 by Sondra Wilson.

Following World War II, from 1945-1949, thirteen trials were held in Nuremberg, located in the German state of Bavaria. There were multiple defendants in the cases,[1] wherein major war criminals were found guilty by the International Military Tribunal, then executed. On September 10, 1947, the US Military Government for Germany created Military Tribunal II-A (later renamed Tribunal II) to try the Einsatzgruppen Case. The 24 defendants were all leaders of the mobile security and killing units of the SS, the Einsatzgruppen.[2]

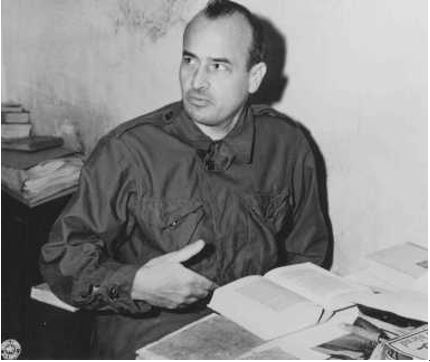

Hans Frank, shown in Figure 1, was an early supporter of the Nazi party (photo shown as right), had studied law & eventually became the personal legal advisor to Adolf Hitler. After the outbreak of World War II, Frank was appointed Governor General of occupied Poland. In this capacity, Frank was responsible for the exploitation & murder of hundreds of thousands of Polish civilians, as well as the deportation & murder of Polish Jews. He was found guilty on counts three and four (war crimes and crimes against humanity) and sentenced to death. Frank was executed on October 16, 1946.[3]

Wilhelm Frick, Reich Minister of the Interior from 1933 to 1943, and Reich Protector for Bohemia and Moravia from 1943 to 1945, in the decisive first years of the Nazi dictatorship, directed legislation that removed Jews from public life, abolished political parties, and sent political dissidents to concentration camps. Frick was found guilty on counts two, three, and four (crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity), then sentenced to death. He was executed on October 16, 1946.[4]

Shown At Left: Wilhelm Frick. Photo Source: https://flowvella.com/s/3li2

Judge Benjamin Kaplan was an Army officer who helped craft the indictment (formal charge or accusation) of the Nazi war criminals who were tried at Nuremberg. He later became a Harvard law professor & served nine years on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.[5] Kaplan charged:

“All the defendants, with divers other persons, during a period of years preceding 8 May 1945, participated as leaders, organizers, instigators, or accomplices in the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy to commit, or which involved the commission of, Crimes against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against Humanity, as defined in the Charter of this Tribunal, and, in accordance with the provisions of the Charter, are individually responsible for their own acts and for all acts committed by any persons in the execution of such plan or conspiracy.”[6]

During the Einsatzgruppen Case, twenty-four defendants were charged under four counts:

- crime against peace

- planning & waging wars of aggression

- war crimes

- crimes against humanity.

They did not include Adolf Hitler, who killed himself by gunshot on 30 April 1945, Heinrich Himmler (head of the SS), or Joseph Goebbels (head of propaganda), who also commit suicide. Martin Bormann, the Nazi party secretary, was tried in absentia – his remains were found many years later in Berlin. Robert Ley, head of the “Strength through Joy” worker movement, hanged himself before the trial started. Hermann Göring, Hitler’s successor, killed himself with a phial of cyanide the night before he was to be executed. Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s former deputy, who flew to Britain in 1941 with what he called a peace plan, was given a life sentence. He killed himself in Spandau prison, Berlin, in 1987. Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect who was responsible for the mass exploitation of forced foreign labour, was jailed for 20 years. The man who supplied the slave labour, Fritz Sauckel, was sentenced to death, as were 12 others.

The Nuremberg tribunal became renown for the “I was only obeying orders” defense, & led to a series of subsequent international conventions on the laws of war, genocide, & human rights, & the setting up of a permanent international criminal court in The Hague (Netherlands).

During the trials, the subordinate officials under Allied Control Council Law No. 10[7] were the subject of considerable controversy in Germany & in the West.

The old Latin maxim of nullum crimen sine lege, nulla poena sine lege was much discussed as a bar to these prosecutions, the theory being that the acts in question were not crimes when committed.[8] The maxim literally translates “no crime or punishment without a law”. In the U.S., this maxim is found in the Ex Post Facto Clauses of Article 1 of The Constitution:

- 9: “No… ex post facto Law shall be passed.”

- 10: “No state shall… pass any… ex post facto law…”

This principle of legality requires, as a prerequisite to just punishment, fair notice to the defendant of the conduct classified as criminal, & the range of punishment attached to it. This principle also finds expression through the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments by way of the “vagueness” doctrine, which is the requirement of reasonable precision in defining criminal conduct. The constitutional requirement of definiteness is violated by a criminal statute that fails to give a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice that his contemplated conduct is forbidden by the statute.[9]

The Superior Orders Defense, in summary, argues that “the acts charged to them were committed under orders from military or civilian superiors to whom a duty of obedience was owed”. The nature of the defense evolves from the duty of obedience which soldiers of all nations owe to their superior officers.[10] In the U.S. military, this duty of obedience is found within the Oaths of Enlistment, yet so is the principle that if such orders violate The Constitution, the officer must “defend… against all enemies, foreign and domestic”:

“I, _____, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to regulations and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. So help me God.”[11]

Deliberate actions such as murder, pillage, & others are clearly known to be in violation of criminal law (municipal or international), so can they ever be subjected to the duty of obedience? To paraphrase the question proposed at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg: “do individuals have international duties which transcend the national obligations of obedience imposed by the State?”

Photos from TIME Magazine, December 10, 1945. Volume XLVI (47) Number 24 Hermann Göring & Rudolf Hess, front row far left, & Hans Frank, in the sunglasses front row fourth from right, are among the Nazis in the dock in Nuremberg, September 1946. Photograph: Eddie Worth/AP: www.anglonautes.eu/history/hist_germany_20_ww2/hist_20_ww2_ger_nuremberg/hist_uk_us_20_ww2_nuremberg.htm

1804-1956: The U.S. Has Consistently Ruled Against ‘Superior Orders’ As Being An Acceptable Defense, When A Crime Is Committed As A Result of The Obedience:

“Superior orders” received its first judicial consideration in a national context, with the earliest modern cases occurring in the United States, in which the defense was generally rejected. In 1804, the Supreme Court in Little v. Barreme[12] held that the captain of a U.S. frigate (warship) who wrongfully captured a neutral ship pursuant to an unauthorized order from the President (Jefferson) was liable for civil damages. After determining that the capture was, in fact, unlawful, Chief Justice Marshall (appointed by John Adams), reversing his earlier thoughts on the matter, concluded, “the instructions cannot change the nature of the transaction, or legalize an act which without those instructions would have been a plain trespass.”[13]

In 1813, again under Chief Justice Marshall, a federal circuit court again, after consideration, rejected this defense in United States v. Jones.[14] There, the crew of an American privateer (a private person or ship engaged in maritime warfare under a commission of war known as a letter of marque) was charged with piracy for stopping a neutral vessel, & then assaulting her captain & crew & stealing merchandise. To the claim that the crew acted pursuant to orders of the captain, the court stated:

“This doctrine, equally alarming and unfounded… is repugnant to reason, and to the positive law of the land. No military or civil officer can command an inferior to violate the laws of his country; nor will such command excuse, much less justify the act…. We do not mean to go further than to say, that the participation of the inferior officer, in an act which he knows, or ought to know to be illegal, will not be excused by the order of his superior.”[15]

Almost four decades later, the Supreme Court, under Roger B. Taney (appointed by Andrew Jackson), again had the question before it in the case of Mitchell v. Harmony.[16] There, the plaintiff left Missouri with considerable livestock & merchandise, intending to trade in Mexico at a time when such trade was legal. While en route, war with Mexico was declared; the Army was sent to overtake him, which it did. After trailing along behind the Army for some time, the plaintiff wished to go his own way, but the defendant, a colonel acting under orders, refused to let him leave, as a result of which his goods were eventually lost. In holding the defendant liable for damages, the court stated:

“Consequently, the order given was an order to do an illegal act; to commit a trespass upon the property of another; and can afford no justification to the person to whom it was executed… And upon principle, independent of the weight of judicial decision, it can never be maintained that a military officer can justify himself for doing an unlawful act, by producing the order of his superior.”[17]

The conclusion of Mitchell v. Harmony was reasserted, in Dow v. Johnson[18], where the Supreme Court released the statement, under Chief Justice Morrison Waite (appointed by Ulysses S. Grant), “We do not controvert the doctrine of Mitchell v. Harmony… ; on the contrary, we approve it.”[19]

In later cases, the courts tended to be somewhat more lenient in their rejection of the defense, but only on the basis that the acts in question were not clearly known to be illegal. In 1889, under Supreme Court Justice Melville Fuller (appointed by Grover Cleveland), in Freeland v. Williams[20] the Supreme Court struck down a judgment entered against a former member of the Confederate Army for taking cattle from the plaintiff under orders from his superior officer.

Later[21], in State of New York v. Jude Tanella (still under Melville Fuller), a federal circuit court acquitted a corporal of manslaughter, when, on orders from his sergeant, he killed a fugitive who had escaped from detention. The basis of the court’s decision was:

“The illegality of the order, if illegal it was, was not so much so as to be apparent and palpable to the commonest understanding. If, then, the petitioners acted under such order in good faith, without any criminal intent, but with an honest purpose to perform a supposed duty, they are not liable to prosecution under the criminal laws of the state.”[22]

There does not appear to have been any substantial change in the attitude of American courts as expressed in the above cases.[23] Even in time of war, “superior orders” has historically not been a defense to a clearly illegal act in American law.

The law in Great Britain has been quite similar. In the early case of Ensign Maxwell, who, under orders, killed a French prisoner during the Napoleonic Wars by firing into a cell, the Scottish court rejected the plea of superior orders, declaring:

“If an officer were to command a soldier to go out to the street & to kill you or me, he would not be bound to obey. It must be a legal order given with reference to the circumstances in which he is placed; and thus every officer has a discretion to disobey orders against the known laws of the land.”[24] [25]

Appendices

Figure 1. Defendant Hans Frank, former Governor General of occupied Poland, in his cell at the Nuremberg prison. November 24, 1945.— National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Md.

References

[1]NPR: “The Last Nuremberg Prosecutor Has 3 Words Of Advice: ‘Law Not War’”. Heard on Morning Edition: http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/10/18/

497938049/the-last-nuremberg-prosecutor-has-3-words-of-advice-law-not-war

[2]United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Encyclopedia, “SUBSEQUENT NUREMBERG PROCEEDINGS, CASE #9, THE EINSATZGRUPPEN CASE United States v. Otto Ohlendorf, et al.“: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007080

[3]“ “, “HANS FRANK”: https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007108

[4] “ “, “WILHELM FRICK”: https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007109

[5] The New York Times, “Benjamin Kaplan, Crucial Figure in Nazi Trials, Dies at 99” by Bruce Weber, 8-24-2010: www.nytimes.com/2010/08/25/us/25kaplan.html

[6] Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, The Avalon Project,Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 1

Indictment : Count One, HE COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY”: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/count1.asp

[7] Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, The Avalon Project, “Nuremberg Trials Final Report Appendix D : Control Council Law No. 10, PUNISHMENT OF PERSONS GUILTY OF WAR CRIMES, CRIMES AGAINST PEACE AND AGAINST HUMANITY”: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/imt10.asp

[8] Alan M. Wilner, Superior Orders as a Defense to Violations of International Criminal Law, 26 Md. L. Rev. 127 (1966): http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol26/iss2/5

[9] USlegal “Nullum Crimen Sine Lege, Nulla Poena Sine Lege Law and Legal Definition”: https://definitions.uslegal.com/n/nullum-crimen-sine-lege-nulla-poena-sine-lege/

[10] Alan M. Wilner, Superior Orders as a Defense to Violations of International Criminal Law, 26 Md. L. Rev. 127 (1966): http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol26/iss2/5

[11] U.S. Army, Army Values, “Oath of Enlistment”: https://www.army.mil/values/oath.html

[12] Official Citation: Little v. Barreme, 2 Cranch 170 (1804): https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/6/170/case.html

[13] Id. at 178.

[14] Official Citation: United States v. Jones, 36 Fed. Cas. 653 (No. 15494) (C.C.D. Pa. 1813).

[15] Id. at 657.

[16] Official Citation: Mitchell v. Harmony, 13 How. 115 (1852)

[17] Id. at 136

[18] Official Citation: Dow v. Johnson, 100 U. S. 158 (1880)

[19] Id. at 169.

[20] Official Citation: Freeland v. Williams, 131 U. S. 405 (1889)

[21] Official Citation: State of New York v. Jude Tanella In re Fair, 100 Fed. 149 (D. Neb. 1900): http://aele.org/tanella-2nd.html

[22] Id. at 155 (emphasis added).

[23] See United States v. Clark, 31 Fed. 710 (E.D. Mich. 1887) ; Neu v. McCarthy, 309 Mass. 17, 33 N.E.2d 570 (1941) ; Commonwealth v. Shortall, 206 Pa. 165, 55 Ati. 952 (1903).

[24] II BUCHANAN, REPORTS Or RiwARKABL TRIALS 3, 58 (1813).

[25] Alan M. Wilner, Superior Orders as a Defense to Violations of International Criminal Law, 26 Md. L. Rev. 127 (1966): http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol26/iss2/5