Civilian Conservation Corps. (“C.C.C.”) was a historic public work relief program accredited with having equipped more than 3 million men ages 18-25 with jobs which provided real-world skills that solved environmental problems, rebuilt (and built) infrastructure, and helped dig the country out of The Great Depression.

Under the guidance of the U.S. Forest Service, National Parks Service, Department of the Interior, and the USDA, CCC employees:

- fought forest fires

- planted more than 3 billion trees

- cleared and maintained access roads

- re-seeded grazing lands

- implemented soil-erosion controls

- built wildlife refuges, fish-rearing facilities, water storage basins, and animal shelters.

To encourage all citizens to get out and enjoy the great outdoors, C.C.C. employees also developed hiking trails and built bridges and campground facilities in more than 800 National Parks, thus shaping the modern national and state park systems we enjoy today.

Some corpsmen received supplemental basic and vocational education. It is estimated that some 57,000 illiterate men learned to read and write in C.C.C. camps. [1] The C.C.C. was implemented by the 32nd President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and is often seen as the most successful agency within The New Deal.

A short two-part documentary,

followed by additional information:

Part 2:

Native Americans & The C.C.C.

Backstory, Logistics, & Outcome:

Still living during a time of segregation, the C.C.C. marks an attempted emergence toward self-sufficiency & dissemination of practical, needed work-related skills to people that would stick with them & serve them their entire lives.

The CCC enrolled World War I Army veterans, skilled foresters & craftsmen, & roughly 88,000 Native Americans living on reservations.

Despite an amendment outlawing racial discrimination in the CCC, young African American enrollees lived and worked in separate camps. In the 1930s, the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t think of segregation as racial discrimination.

Women were prohibited from joining the CCC. [1]

The task of invoking radical new measures to solve the problems of the Indians fell to John Collier, author of “A Bill of Rights for Indians“. [2] Appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 to head the Indian Bureau, Collier hoped to correct past wrongs inflicted upon one of the nation’s longest suppressed minorities with a single comprehensive law. The result was the Wheeler-Howard aka Indian Reorganization Act (“I.R.A.”) of 1934, which exemplified Collier’s philosophy and that of the New Deal. It abandoned the allotment system that had dominated federal Indian policy since 1887 and provided a $10 million “revolving fund” to assist Indian cooperation in economic development. The I.R.A. granted the tribes limited home rule by allowing them to adopt their own constitutions and bylaws. All constitutions had to be approved by the secretary of the Interior.

John Collier with Blackfoot Elders in South Dakota to Discuss the Passing of IRA:

Click to Enlarge:

Above photo from History.com utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Commissioner Collier also hoped to reform the entire program of Indian education, however the I.R.A. only established a scholarship fund for higher learning. He had hoped to eliminate Indian boarding schools, develop day schools near the reservations, and encourage Indian children to attend public schools, however it was discovered that additional legislation would be needed to accomplish this. The Johnson-O’Malley Act of 1934 authorized the secretary of the Interior to enter into contracts with states for the improvement of Indian education and welfare. The federal government in turn made payments to school districts where Indian children lived on reservations and attended public day-schools. Because Indian lands held in trust are nontaxable, the schools thereby used the funds in lieu of tax revenue. At the same time the federal government could help establish curriculum standards.

Catholic missionaries in South Dakota especially reacted negatively to Collier’s support of day-schools in place of boarding schools. Much of the controversy involved Article IV of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty: Catholic educational institutions had acquired 80 percent of the total government grant for religious education. When the treaty lapsed, the government planned to withdraw support from the Catholic Indian mission schools —except for physical maintenance. The savings would be used for the care of Indian children attending other parochial schools in all parts of the country. Catholic missionaries vehemently attacked Collier’s program on the grounds that it would endanger the status of mission schools. However, the real reason for the attacks was disdain toward increased aid to Protestant establishments. Many missionaries became antagonistic over the radical new commissioner’s insistence that interference with the Indians’ religious life or ceremonial expression would not be tolerated. Segregating the Indians from white society & condoning old tribal traditions would undermine decades of missionaries’ efforts to Christianize them. The so called pagan cults of the Ghost Dance and the Sun Dance directly conflicted with their teachings, as did the more popular Peyote ceremonies or Native American Church. Once relieved of government restrictions, these ceremonies would again be practiced actively on the reservations. Even with the revived interest in native culture, education, & government, the basic fact remained that, removed from their ancestral ways of life, many native people were starving because they lacked the means to support themselves. The Meriam Report had revealed that the average yearly per capita income of those residents of South Dakota reservations in 1926 was only $166.’ By the 1930s, the ravages of drought & depression had further entrenched the problems. Congress thereby created the Civilian Conservation Corps in March 1933 to relieve “the acute conditions of widespread distress and unemployment… and to provide for the restoration of the country’s depleted natural resources.”

The act did not mention (“Indian”) Tribes, but Collier and J. P. Kinney, director of Forestry, quickly made known to President Roosevelt the urgent need for conservation measures on reservations, insisting that special conditions warranted an independent program under the direction of the Office of Indian Affairs. After careful consideration, Roosevelt authorized the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW), which allowed reservation Indians to direct their own work in separate camps. Not only would Indians do all the labor, but tribal councils would help select the projects. To assist in technical matters the bureau established six district offices in the Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska under the jurisdiction of the Billings, Montana, district. Although given virtually independent action on the reservations, the Indian program had to meet most of the regular CCC regulations. Roosevelt placed the new program on a separate basis primarily because of objections by the Indians to quasi-military camps on their lands. Thus, corps officials exempted workers in the reservation camps from the customary army conditioning period, & at the same time gave preference to Indians for supervisory positions, & a meager subsistence allowance to provide clothing & shelter. Because most of the supervisory jobs required technical skills or knowledge the majority of the Sioux (as the Lakota are referred to in the Treaty) did not possess, U.S. government officials filled these administrative positions. Later, a few Indians completed leadership training courses sponsored by the CCC-ID and advanced to become project managers.

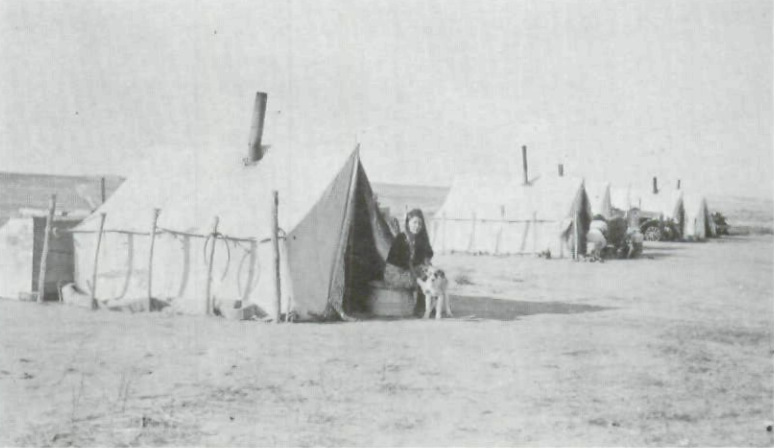

The regular CCC practice of employing 200 men in a camp for six months proved impractical on the sparsely populated reservations. Roosevelt thereby authorized the Indians to be mobilized into work units of 40 to 50 men. Corps officials then established three principle types of domiciles:

- the permanent boarding camp for single men

- the home camp for those desiring to live at home

- the family camp for projects of short duration where the entire household could reside temporarily in tents.

The family camps were popular with the Lakota and at the same time cost the federal government less than permanent units.

Typical CCC-ID Temporary Family Camps at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation:

Above photo from South Dakota State Historical Society utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

However, sanitation conditions in the twenty family units on the Rosebud Reservation in 1937 were deplorable. There were no sewer or water systems and open garbage pits were commonplace. Two agency doctors & four field nurses served the area, but were unavailable to perform services for the CCC-ID camps. To combat these adverse conditions, workers resided in camps for one season, & whenever possible took advantage of living at home. At times this became extremely difficult. For example, at Pine Ridge a work crew even had to carry a two-week food supply with them because of the rough terrain and roads. Regardless of the conditions and type of work camps, the CCC-ID had more applicants than it could possibly accommodate. To allow the maximum number of Indians on the payroll, officials would stagger employment of CCC-ID enrollees & allow them to work on neighboring reservations.

The basic wage was $30.00 a month, or $1.50 per day— plus 60¢ subsidy for those living at home— for twenty workdays a month. Enrollees also received $1.00 to $2.00 per day for use of their own teams of horses. Some eventually advanced to assistant foreman at $135.00 per month and a few to group foreman at $167.00.

The CCC-ID was the first emergency legislation from which the tribes benefited directly. Heretofore, CCC-ID funds could only be used for the necessities of life, but large-scale projects could now be undertaken to protect forest, range, and farm lands.

At first, few native people knew how to operate the crude equipment necessary for road and dam construction, and as a consequence hundreds of small earth dams had to be rebuilt. By 1936 they had generally gained sufficient confidence and experience to undertake more elaborate projects. Heavier and more sophisticated machinery replaced horse-drawn scrappers, and concrete spillways became a regular addition to the larger dams constructed on the Red Earth and Cheyenne rivers. Such structures marked a change in the original purpose of the CCC-ID in that the maximum amount of money should go into payrolls, not expensive equipment. Building these larger projects necessitated the use of heavy equipment and skilled workers. Again, many of the Sioux were inexperienced in operating earth movers, dump trucks, cranes, and large cement mixers, so non-Indians filled some of the positions.

Workers Construct a Wooden Spillway Gate So Water in the Reservoir Can be Used for Irrigation at Standing Rock:

Above photo from South Dakota Historical Society utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Tom C. White, district coordinator for Billings, requested new and expanded production roles. After Washington accepted most of his proposals, he then sought permission to hire skilled whites to operate the machinery rather than train Indians for such duties. His policy was to keep enrollees in unskilled labor so that equipment would not be damaged or production delayed. This thoughtlessness for the welfare of the enrollees carried over into the education program, which lagged far behind other areas in off-duty activities. Any encouragement in vocational & educational training of CCC-ID enrollees came from reservation officials, not the Billings headquarters. Under White’s insistence several small irrigated gardens, from two to fifteen acres each, were constructed on every South Dakota reservation by the end of 1936. Responsibility for the gardens— usually small pumping projects along the Missouri River— fell to the reservation superintendents. The Lakota normally operated the gardens on a family basis except in a few instances where they participated in community enterprises with the produce being shared equally by everybody. All gardens yielded more than enough vegetables for personal consumption, thus allowing a surplus for marketing on the reservations. In addition to furnishing water for irrigation, the small storage dams provided a dependable water supply for both domestic and stock use, as well as improving the health and sanitation conditions for many reservation residents.

The CCC-ID also cooperated directly with the Relief and Rehabilitation Program to provide facilities and opportunities for destitute Indians. Together these agencies strove to expand the tribes’ economies by developing truck-garden farms for food production & livestock industries for cash needs. The federal government selected the participants for the enterprises, with landless Indians receiving preferences, who would then come under direct supervision of the reservation superintendent. The Enrollee Program provided for the Indians’ training, recreation, and welfare and was an integral part of the CCC-ID. Its major objective was to make natives more employable while presenting useful information applicable to everyday living. Because many of the enrollees could not read or write English, the program experienced more difficulty operating among the Lakota than with any other group in the country.

Despite White’s insistence that production activities must dominate the CCC-ID camps, educational programs did much to boost the welfare & morale throughout the reservations. Corps officials provided a realistic concept of education that corresponded to the interests and needs of the enrollees and the reservations. The scope of the training was wider than the local conservation program itself. Many project leaders, truck drivers, and machine operators held first aid certificates and officials in the Extension Department sponsored educational discussion groups and weekend leadership workshops with supervisors, farm extension agents, physicians, and various government employees serving as classroom instructors. Native people received training in farm maintenance, carpentry, tractor operation and repair, Red Cross safety, & a variety of other fields. By the end of the 1930s officials at Pine Ridge and Cheyenne River had used CCC-ID funds to equip a truck with a traveling library.

Enrollees on the Standing Rock Reservation Participate in a First Aid Class in 1937:

Above photo from South Dakota State Historical Society utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

Camp administrators purchased a movie projector. Educational movies on health, safety, gardening, rodent control as well as films on CCC-ID activities were shown on a weekly basis. Entertaining movies, a novel experience for the Lakota, were viewed with mixed reactions. While watching a film about Yellowstone National Park, a number of people in the audience did not believe there were such things as geysers. Only after careful explanation and a reshowing of the film did the Cheyenne River officers convince the Indians that there were natural hot springs that intermittently ejected a column of water and steam. Multiple games were taught & played—from baseball to “ice snakes” but native songs and dances like the “Omaha,” the “Grass,” and the “Rabbit” were most popular.

The relaxed nature of the camps allowed considerable flexibility and freedom. Training activities brought a fuller understanding of the bureau’s intentions & helped remove some of the Indians’ suspicions. In compliance to the president’s directive, Fechner, director of the corps, notified his organization that it must employ one enrollee for every $930 received in CCC-ID funds.

With World War II approaching the CCC-ID became increasingly involved in war production activities. Government officials used the corps’ existing facilities to teach various national defense courses, while opportunities opened up for enrollees in the private sector of the economy. Indians obtained employment as carpenters, truck drivers, mechanics, & welders —an impossibility during the depression era. After Congress completely cut the 1942 CCC-ID budget, it was only a matter of time before field officers halted production and laid off the enrollees & supervisory personnel.

In the midst of the activities to support the war effort, the Indian CCC came under harsh criticism from the Rosebud Tribal Council who charged that the uncertainty of the work benefited few Indians and that the dams served only the large cattlemen who leased the land. Government officials argued that the CCC-ID provided the Indians with a substantial portion of their income during the depression & that without the dams nobody would rent the grazing land. Probably the most legitimate complaints were against the supervisory personnel’s excessive spending for machinery to construct large “show projects” that required skilled non-Indian labor. Likewise, officials used funds for cars and home improvements while most Indians lived in tents. The council’s proposal to redraft the CCC-ID came too late, for the program ended on 10 July 1942.

CCC-ID left the Sioux after nine years of conservation and rehabilitation. Although there were diverse opinions over the effectiveness of the corps, it undoubtedly was one of the most popular and productive Indian programs of the decade. In South Dakota the CCC-ID employed 8,405 Indians and spent over $4,500,000 on the Rosebud, Standing Rock, and Pine Ridge reservations alone.

Some Indians who planted gardens began using their CCC-ID earnings to purchase vegetables and thus neglected their crops. In such situations the program was virtually ineffective. Despite some shortcomings the CCC-ID kept many poverty stricken Indians from starving and supplied hundreds of enrollees with skills & proper work habits necessary for off reservation jobs. That the helped corps give the Lakota confidence & a new outlook on life became evident by the great exodus of Indian men from the reservation to military service & private industries. Moreover, it helped reverse their downward drift and gave them something to help them get back on their feet during the desperate years of the 1930s after having fast numerous historical hardships, injustices, and trauma. [3]

African Americans in the CCC:

250,000 African Americans who were enrolled in nearly 150 all-black CCC companies. These enrollees contributed to the protection, conservation & development of the country’s environmental resources. Enrollees planted trees, fought fires, and took part in pest eradication projects. They built and improved park and recreation areas, constructed roads, built lookout towers, and strung telephone and electric wires. Money sent home by CCC enrollees assisted families hard-hit by the depression. CCC camps provided enrollees with educational, recreational and job training opportunities.

Young men of Company 2314-C, Kane, Pennsylvania, study radio code, which enabled them to run the camp radio station. National Archives

Young men of Company 2314-C, Kane, Pennsylvania, study radio code, which enabled them to run the camp radio station. National Archives

African American CCC members performed their duties in a society divided by race, and often in the presence of officially sanctioned racism. Black membership in the CCC was set at ten percent of the overall membership—roughly proportional to the percentage of African Americans in the national population. However, because the economic conditions of blacks were disproportionately worse than those of whites, this race-based quota system did not adequately address the relief needs of African American youth. When the CCC began, few efforts were made to actively recruit African Americans. Many states, particularly in the South, passed over qualified black applicants to enroll whites. Black CCC enrollees routinely faced hostile local communities, endured the racist attitudes of individual CCC, Army and Forest Service supervisors, and found limited opportunities for assuming leadership positions within the CCC’s administrative structure. This inhospitable environment was aided by the absence of a sustained commitment on the part of the Roosevelt Administration to end racist practices within the CCC.

In the early years of the CCC some camps were integrated, but prompted by local complaints and the views of the US Army and CCC administrators, integrated CCC camps were disbanded in July, 1935, when CCC Director Robert Fechner issued a directive ordering the “complete segregation of colored and white enrollees.” While the law establishing the CCC contained a clause outlawing discrimination based upon race; the CCC held that “segregation is not discrimination” (see Fechner’s letter to NAACP leader Thomas Griffith). Although the CCC’s Jim Crow policy prompted complaints from black and white civil rights activists, segregation remained the rule throughout the life of the CCC. [4]

References:

All material utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use, for First Amendment purposes.

[1]: History.com, “Civilian Conservation Corps.”: www.history.com/topics/civilian-conservation-corps

[2]: History Matters, “A Bill of Rights for the Indians: John Collier Envisions an Indian New Deal”: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5059/

Photo of John Collier with Blackfoot Chiefs from History.com, “Native American Cultures>Native AmericanLegislation”: www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-cultures/pictures/native-american-legislation/john-collier-with-blackfoot-indians

[3]: South Dakota State Historical Society, “The Sioux and the Indian-CCC” by ROGER BROMERT: http://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-8-4/the-sioux-and-the-indian-ccc/vol-08-no-4-the-sioux-and-the-indian-ccc.pdf

[4]: FDR Presidential Library & Museum, “African Americans in the

Civilian Conservation Corps”: http://newdeal.feri.org/aaccc/

Back to Civilian Restoration Corps

– or –