Not long ago, across more than 750,000 square miles, the heartland of the continent was a vast sea of prairie grass, interrupted here & there by mountainous terrain & winding, forested river bottoms.

Click to Enlarge:

Above photo from 7 Themes utilized according to Fair Use.

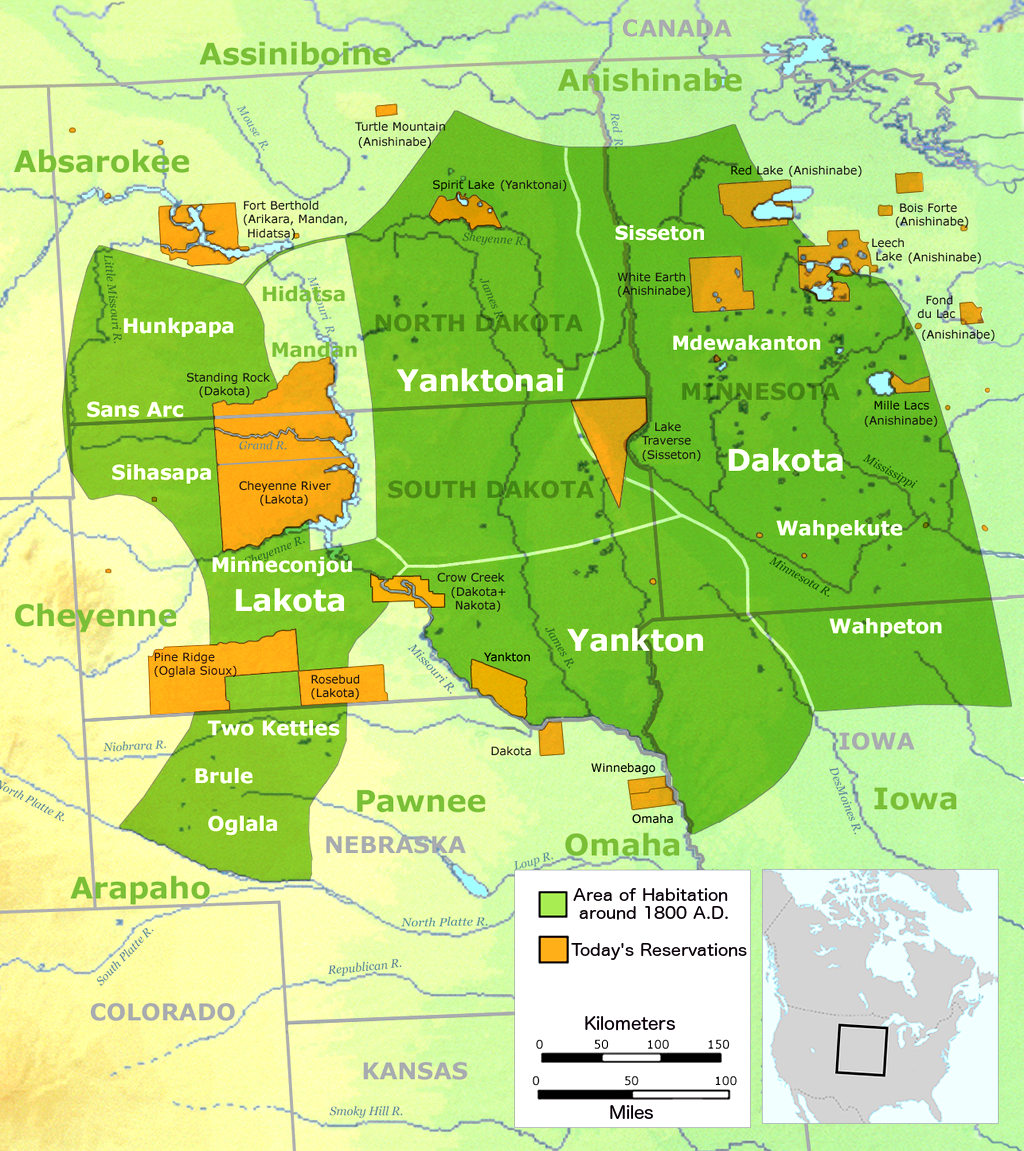

The Oceti Sakowin (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota) inhabited a large portion of the northern Great Plains (learn more). The Crow were directly to the west, Mandan & Hidatsa to the north, & Ponca, Omaha, & Pawnee to the south. [1]

Above map from WikiWand utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Tribes subsisted from, observed, & derived their spiritual understanding of the world — their connection — through fulfilling the integral roles they each played among & alongside these prairies & surrounding ecosystems.

Above photo from ImageKind Canvas Prints utilized respectfully with regard to Fair Use.

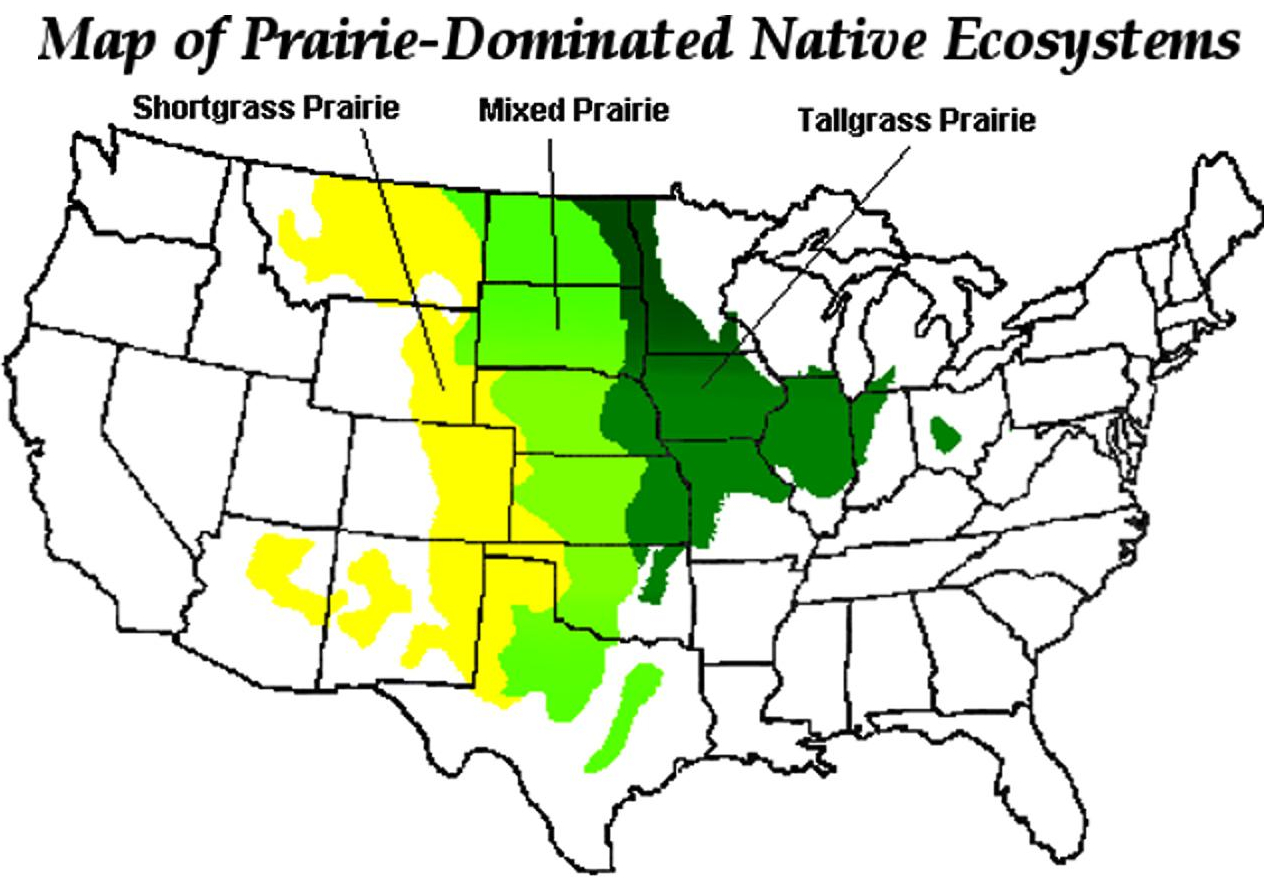

The three main prairie-dominated ecosystems included western shortgrass prairies, midland mixed prairies (containing both shortgrass & tallgrass species), and, to the east, tallgrass prairies:

Above map from Midwestern Regional Climate Change utilized according to Fair Use.

Approximately 40% of the U.S. land mass was covered in prairie, with tallgrass prairie accounting for ~142 million acres.

- Iowa had the largest percentage of its area covered by tallgrass prairie, with around 30 million acres.

- Over 100 plant species can occur in a prairie of less than 5 acres!

- The major grasses of the tallgrass prairie are the big bluestem, the little bluestem, Indiangrass and switchgrass.

- These tall grasses can grow as tall as ten feet and average a height of six to eight feet.

- The soil underneath the prairie is a dense tangle of roots and bulbs.

- Some prairie plants put out roots that extend 12 feet below the prairie surface. Each year some of the roots die. Large quantities of organic matter are added to the soil as they decompose —thereby producing rich and fertile soil.

- At least 30 million bison grazed on the plains & prairies when European explorers first arrived, as well as millions of elk and millions of pronghorn. [2] Selective grazing by these animals naturally promoted the growth of other plants that were exposed to more sunlight as the grasses were kept short, thus increasing the diversity. [3] Grazing is an integral part of the prairie ecosystem, and also increases the growth of prairie plants.

- Prairie dogs also perform a vital ecological role to which more than 130 species throughout the prairie depend on to survive. [2]

- Prairies are also home to a variety of native butterflies. Due to the vitality of their apparent ecological role and intrinsic beauty, it is difficult to truly know “where the flower stops and the butterfly begins”:

Click to Enlarge:

Above graphic from Tabletop Whale utilized respectfully according to Fair Use.

The endless flatness throughout the midwest (Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Illinois, South Dakota, etc.) was created by glaciers, which deposited seed, soil, & sediment as they melted — thus introducing the prairies. [4]

Above photo from Desktop Wallpapers utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

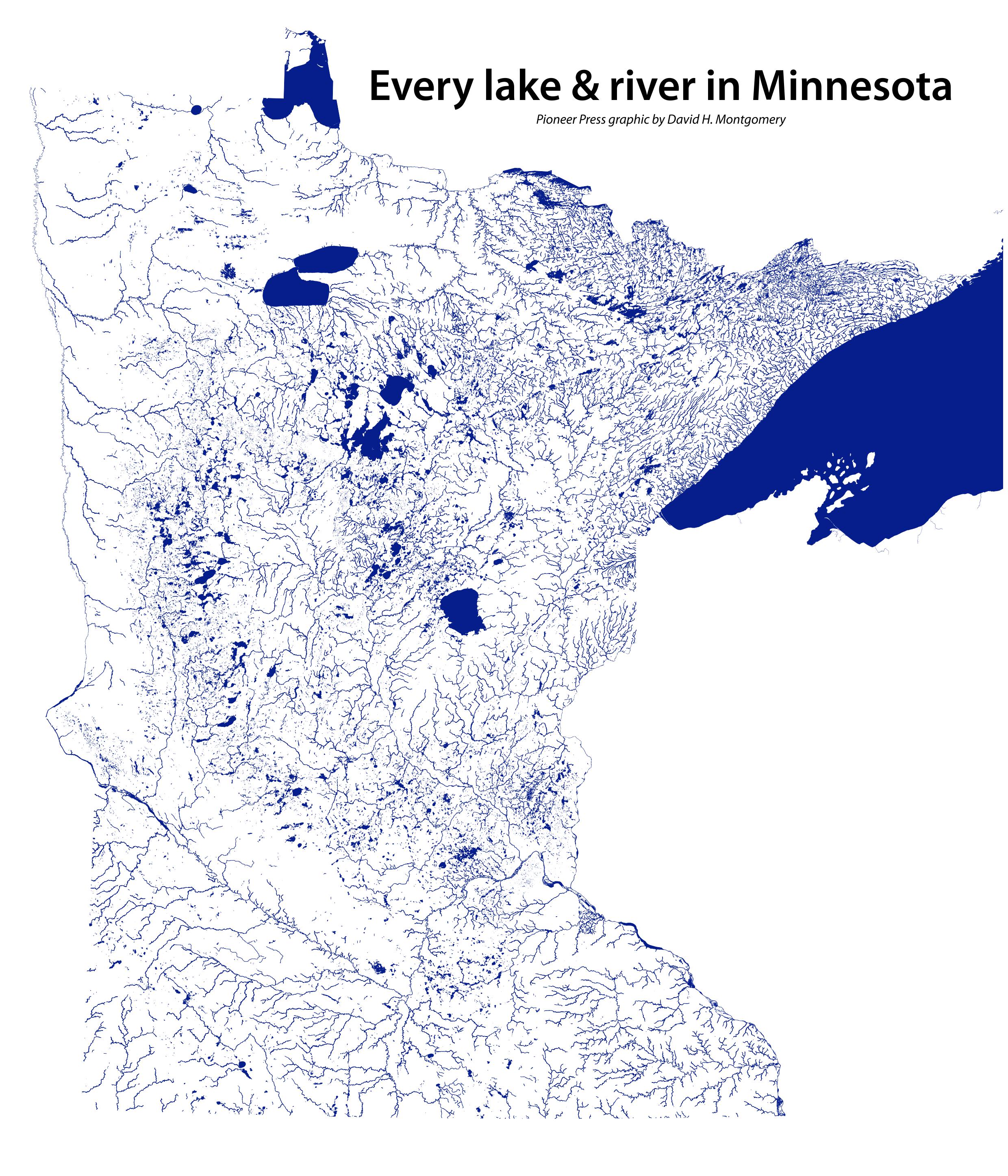

Those enormous ice sheets were, at their maximum, 5,000 to 10,000 feet thick, covering hundreds of thousands of square miles. They released tremendous amounts of water, forming lakes & other bodies of water throughout Minnesota, North Dakota, Iowa, Illinois, & surrounding states – including the Great Lakes! [5] Ever wondered why the Los Angeles “Lakers” are called the “Lakers” when clearly they’re located in a dry desert where there are no lakes? This is because in 1960 the Minnesota Lakers moved to L.A. from “The Land of 10,000 Lakes” [6] – all of which were left behind by glacial melt:

Minnesota

“The Land of 10,000 Lakes”:

Above map from Twin Cities Pioneer Press utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

The materials the glaciers deposited which they had carried with them & picked up along the way helped form the richest agricultural soil in the world. During a prolonged, hot, dry period around 8,300 years ago, prairie became the dominant vegetation type throughout the midwest. The flat to gently rolling landscape created by the glaciers provided ideal terrain for the movement of fire, an agent that shaped and perpetuated the prairies for the next 8,000 years. [4]

Above photo by Dan Charles utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Fires Play a Vital Ecological Role:

Fire & prairie plants are mutually dependent one another. Many prairie fires were caused by the intense lightning storms the midwest is known for:

Above photo from ABC News utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

- Fire stimulates growth of prairie plants by removing dead plant material, allowing sunlight to penetrate to the black earth that follows the burn in order to warm the ground & stimulate dormant plants to sprout & grow.

- The tied-up nutrients that would take months or years to decay are within seconds turned to ash & in a form usable to plants.

- Fire promotes the germination of many prairie plant seeds by removing the seed coat.

- Without fire, the grasses & other fire-adapted prairie plants would eventually become shaded out by trees, & thus forested areas & scrublands would replace the prairies altogether. [3]

- Prairie fires can move as fast as 600 feet per minute and burn as hot as 700 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Prairie fire is an important ingredient in the renewal of the prairie.

- Fire does not kill prairie grasses because they grow from the stem up rather than from the tips of the blade. [2]

- Ranchers today purposefully start fires to improve cattle forage and for general upkeep of prairie health. [7]

Native Tribes

Strategically Lit Fires to Manage Prairie Ecosystems:

At certain times of the year, particularly in the spring, it was a distinct advantage to set fire to the dead, dry stalks left from the previous year to stimulate the growth of nutritious new grass. [8] Grazing animals were naturally attracted to areas that had been burned especially during times of regrowth. [3]

Above painting: “The Grass Fire” by Frederic Remington (1908)

Above painting: “The Grass Fire” by Frederic Remington (1908)

In late summer & fall, fires were also set to provide habitat for animals such as bison, elk, & deer, to reduce danger of wildfire, to increase ease of travel, & also to increase visibility & safety. [3]

Purposeful fires were not just set by plains tribes: they were periodically employed by various tribes from coast to coast. Many burns were performed in late spring just before new growth appears, while in areas that are drier fires tended to be set during the late summer or early fall since the main growth of plants & grasses occurs throughout winter. Burns were performed either yearly, every other year, or intervals as long as five years, depending on the tribe and ecosystem. [9]

Devastating Ecological Loss:

- The majority has been caused by livestock & feed crop industries.

- Much has been caused by urban development.

- In Iowa, 99.9 percent of the historic natural landscape is gone.

- Today, only about one percent of the North American prairies still exist.

- Prairie chickens once flourished on the grasslands. As with several other species, as the grass disappeared, so did the prairie chicken. Today, only about 400,000 survive in the entire country, in 11 states. [2]

Above photo by Jeff Dyck utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Above photo by Jeff Dyck utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Ecological Restoration – Let’s Do This!

Our organization, Wild Willpower, has recently created a plan and petition to “transfer subsidies from livestock & feed crop industries to native animal & habitat restoration projects“. Please take a moment to read & sign.

Prairie Restoration – Organizations Already Involved:

The following organizations within the Mississippi River Basin have been working for years to restore native ecosystems:

- Illinois – Chicago Wilderness Prairie Restoration

- Illinois – Midewin Prairie Restoration

- Iowa Prairie Network (IPN) – grassroots, volunteer organization dedicated to the preservation of Iowa’s prairie heritage. Formed in 1990 by Iowans concerned their prairie heritage was disappearing. Brings those who know about prairie together with those who want to learn, to create a network of advocacy.

- Minnesota – Prairie Restoration, inc. – “Restoring the Minnesota landscape since 1977”

- Montana (Bozeman) – American Prairie Reserve

- Iowa – Grinnell College Prairie Restoration

- Michigan – Asylum Lake Preserve

- Texas – San Antonio Missions National Historical Park – National Park Service

- Minnesota – “Mississippi River Prairie Restoration” – National Park Service

- Kansas – “Bottomland Prairie Restoration” – National Park Service

- Have your organization listed here by emailing Distance@WildWillpower.org with “PRAIRIE RESTORATION” written in the subject line.

The Process of Prairie Restoration:

First, here’s a collection of

Process:

North Dakota Parks and Recreation is partnered with ND Game and Fish Department to restore native prairies at 6 state parks including Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park, Cross Ranch, Fort Stevenson, Lake Sakakawea, Icelandic and Turtle River State Parks. Here is the process for restoration they use:

- The process begins with over a year of rigorous weed control to get the sites ready for planting. Dead vegetation is often removed using prescribed fire.

- When the sites are just about ready for planting they may be lightly disked and harrowed using a variety of different equipment.

- High diversity native seed selection is based on individual site characteristics. The native seed mixture is obtained from local seed sources.

- Mowing once in the year of planting helps to reduce competition for sunlight and speed development of certain prairie plants.

- Once established, native seed is often hand broadcasted or seeded with a no-till drill.

- During the first two years, a planted prairie is usually flush with fast-growing, weeds and non-native species such as thistle, clover, wormwood and alfalfa. Hidden below the weed canopy, however, are seedlings of the slower developing prairie plants.

- By the third year after planting, prairie grasses and wildflowers begin to out-compete and replace the weedy species. [10]

References:

[1]: Dreamcatchers.org, “An Introduction to Lakota Culture and History”: www.dream-catchers.org/lakota-history/

[2]: Camp Silos, “Prairie – Quick Facts”: http://campsilos.org/mod1/students/index.shtml

[3]: Friends of Neil Smith National Wildlife Refuge, “Tallgrass Prairie”: www.tallgrass.org/plants/

[4]: University of Illinois “From Glaciers to Big Bluestem: The Prairies of Illinois”: https://web.extension.illinois.edu/illinoissteward/openarticle.cfm?ArticleID=517

[5]: Great River – Mississippi River Tidbits, “Glaciers Left Their Mark on the Mississippi River” by Pat Middleton, Ruth Nissen, Wisconsin DNR, and other Contributors: http://greatriver.com/Ice_Age/glacier.htm

[6]: NBA.com, “All-Time Winning Streaks” March 19, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2008: www.nba.com/news/winning_streaks.html

[7]: National Park Service, Tallgrass Prairie, “Fire and Grazing in the Prairie”: https://www.nps.gov/tapr/learn/nature/fire-and-grazing-in-the-prairie.htm

[8]: Amon Carter American Museum of Art, “Frederic S. Remington (1861–1909) – ‘The Grass Fire‘ (1908) Oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas”: www.cartermuseum.org/artworks/2440

[9]: “Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire” (1982) by Stephen J. Pyne, Princeton University Press. Chapter 2 “The Fire from Asia”, pages 79-80: www.wildlandfire.com/docs/biblio_indianfire.htm

[10]: Natural Resources News – Prairie Restoration Projects: www.parkrec.nd.gov/nature/attachments/news_archive/prairie_restoration_fall_2010.pdf