Classified amongst the Scuiridae (squirrel) family, their other biological relatives include groundhogs, chipmunks, marmots and woodchucks.

Click to Enlarge:

Above photo from World Wildlife Federation utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

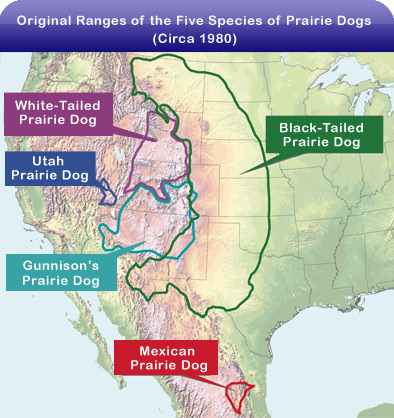

Above map from Prairie Dog Coalition utilized respectfully in accordance with Fair Use.

Ecological Role:

-

Prairie dogs gravitated to the patches of close-cropped grass left by grazing bison where they could watch for prowling predators.

-

Prior to pioneer settlement, some five billion prairie dogs in extensive colonies spread across hundreds of miles of prairie.

-

Saving prairie dogs means saving prairie wildlife. Other creatures have suffered due in good part to the prairie dogs’ decline. For example, the burrowing owl roosts and nests in prairie dog town burrows.

-

Other animals such as hawks, foxes and ferrets that hunt prairie dogs, disappear when the prairie dog population diminishes. [1]

Their intricate underground colonies—called prairie dog towns—create shelter for jackrabbits, toads, and rattlesnakes. The bare patches of ground created by their grazing and burrowing attract certain insects that feed a variety of birds. And prairie dogs themselves are a key food source for everything from coyotes to hawks to endangered black-footed ferrets. [2]

“These animals support at least 136 other species through their various activities,” said Kristy Bly, a WWF senior wildlife conservation biologist.

They’re fast, skilled fighters armed with sharp claws and powerful teeth.

Threats:

Their historical range has shrunk by more than 95%

There used to be hundreds of millions of prairie dogs in North America. European settlers traveling through the West wrote about passing through massive prairie dog colonies, some of which extended for miles. But over time, their range has shrunk to less than 5% of its original extent due to a host of pressures, including habitat encroachment by humans.

They’re threatened by the same plague that caused the Black Death in Europe

In the late 1800s, the bubonic plague entered North America via rats aboard European ships. It quickly spread through wild mammal populations, including black-tailed prairie dogs in the northern Great Plains. The disease is still rampant in large tracts of the region, and tends to wipe out entire prairie dog colonies when it strikes. [3]

Our nation’s 17 Great Plains national grasslands are managed by the U.S. Forest Service. These 3.5 million acres of public land are prime habitat for prairie dogs and other wildlife. As the main public lands in a region dominated by private land, the national grasslands are critical for maintaining healthy wildlife populations. The Forest Service manages the national grasslands more for livestock and energy development than for wildlife. As a result, the agency continues to poison native prairie dogs using taxpayers’ money because they are seen as competition with livestock for grass and because neighboring private landowners do not want the colonies spreading onto their properties.

The rarest and smallest of the five U.S. species of prairie dog–the Utah Prairie Dog–isn’t getting endangered species status, despite years of litigation. Instead, the new rules keep the status quo and codify some restrictions that were already effectively in place.

About 42,000 of these little guys with black eyebrows chatter in three districts, but the colonies are spotty and the numbers not universally accepted. When they were first protected in 1973, only 37 colonies survived, thanks to a massive, 50-year eradication campaign by ranchers and the U.S.D.A.’s Wildlife Services. Now you might be able to see them at Bryce Canyon National Park.

The FWS, led by rancher Ken Salazar, reasoned once again that the best way to protect prairie dogs is by not really protecting them and appeasing ranchers instead. Doug Messerly, who works for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, told the AP that “the best way to help the prairie dogs is minimize conflicts, especially with farmers” and “balance” economic interest.

The new rule does make permanent some things Utah was doing already to help the prairie dog. Farmers and ranchers have to show physical or economic damage before killing up to 36% of the colony. But, they can still kill up to 6,000 and do it within a half mile of the restoration zones. And it’s okay if they do it by mistake. If they were declared endangered, you just couldn’t shoot them. [4]

They’re targeted by poisoning campaigns perpetuating myths that grazing cattle frequently trip on their burrow entrances or that prairie dogs and other grazers can’t co-exist. Their colonies are bulldozed over for housing developments. Shooting them for sport is a common practice.

Once spread over 12 western states and Mexico and Canada, today they occupy 2 to 8 percent of their historic ranges, with populations down by 95 percent.[5]

Restoration Efforts:

Poisoning prairie dogs can be bad for the environment, expensive, and rarely offers a long-term solution. Defenders of Wildlife is working with a handful of national grasslands on nonlethal alternatives to poisoning. For instance , because prairie dogs hesitate to make homes in or go through tall grass, creating tall-grass buffers between prairie dog colonies and adjacent private properties is one way to keep prairie dogs out of where they are not wanted without resorting to killing them. Growing tall grass is difficult in areas frequented by grazing livestock, so Defenders has purchased and installed several miles of solar-powered portable electric fencing along buffer areas to keep livestock out, allowing the grass to grow tall.

Defenders also promotes relocation rather than poisoning of prairie dogs from conflict areas to core areas that are fully protected. We have helped move hundreds of prairie dogs out of harm’s way. [3]

WildEarth Guardians, one of the groups that’s been fighting for the Utah Prairie Dog, is disappointed. Their ESA expert Taylor Jones, said in a statement: “these proposed amendments don’t go far enough. No matter how you dress it up, the rule would still allow shooting of a highly imperiled, ecologically important species, which is indefensible. Rather than continue to cast this keystone species as a nuisance, the Service should promptly return them to endangered status under the ESA.”

-

1973 The Utah prairie dog (Cynomys parvidens) was listed as an endangered species

-

1984 Downgraded to threatened, with a special rule under section 4(d) that allowed regulated take of up to 5,000 animals annually on private lands in Iron County, Utah.

-

1991 Take upped to 6,000 for the whole range

-

2003 Forest Guardians sue to upgrade to endangered

-

2007 FWS says no to endangered status

-

2010 Federal court says no to the FWS refusal, but the FWS goes five miles out of its way to note that the judge “noted that although the level of take allowed in the 1991 special rule may not be biologically sound, some permitted take is advantageous to the Utah prairie dogs’ recovery. The court specifically noted that controlled take can stimulate population growth, reduce high-density populations prone to decimation by plague, and, consequently, curb the species’ boom- and-bust population cycle.”

-

2011 FWS again says no to endangered status, but codifies some existing, de facto restrictions. [4]

Reproduction:

Their entire mating season is just an hour long

In contrast with popular perceptions of prairie dogs as fast-multiplying rodents, these animals actually mate just once a year, in early winter. Females go into estrus for a single hour. They then have litters of three to eight pups—usually only half of which survive their first year.

They live in tight-knit family groups called coteries

The average coterie tends to have one or two breeding males, several breeding females, and the females’ new pups. Males tend to jump from coterie to coterie—but the females stick together for life.

Facts:

Their vocabulary is more advanced than any other animal language that’s been decoded

To a human ear, prairie dogs’ squeaky calls sound simple and repetitive. But recent research has found that those calls can convey incredibly descriptive details. Prairie dogs can alert one another, for example, that there’s not just a human approaching their burrows, but a tall human wearing the color blue.

Black-footed ferrets depend on prairie dogs—and we’re working to protect both species

Prairie dogs are the primary source of food and habitat for endangered black-footed ferrets. At Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, WWF is collaborating with tribal partners to monitor the health of prairie dog colonies where black-footed ferrets live—and identify new areas where ferrets could be released. In September 2015, new ferrets were released into a healthy prairie dog colony, and quickly darted down the holes. [2]

References:

[1]: Camp Silos, “Prairie – Quick Facts”: http://campsilos.org/mod1/students/index.shtml

[2]: World Wildlife Federation, “8 Surprising Prairie Dog Facts” by Sarah Wade: www.worldwildlife.org/stories/8-surprising-prairie-dog-facts

[3]: Defenders of Wildlife, “What Defenders is Doing to Help Prairie Dogs”: www.defenders.org/prairie-dog/what-defenders-doing-help

[4]: Animal Tourism, “Rarest US prairie dog doesn’t get endangered status”: http://animaltourism.com/news/2011/06/06/utah-prairie-do

[5]: Humane Society of the United States’ Prairie Dog Coalition, “Five Ways the HSUS Prairie Dog Coalition Is Working to Save an Iconic Species”: www.humanesociety.org/about/departments/prairie_dog_coalition/five-ways-we-are-saving-prairie-dogs.html?credit=web_id271877979